Written by R.T. Watson. This article first appeared in Bloomberg News.

A bid by China to clean up pollution in its biggest cities and industrial towns is fueling a push to mine resource riches on the other side of the globe in the Amazon rainforest — one of the most environmentally sensitive areas on Earth.

Smog-laden skies across the world’s most-populated country prompted the government to impose curbs on a domestic steel industry that uses coal-fired blast furnaces to melt iron ore. That’s led to increased demand for higher-grade ore from overseas that can produce more steel with fewer emissions, and profit margins on those shipments have surged.

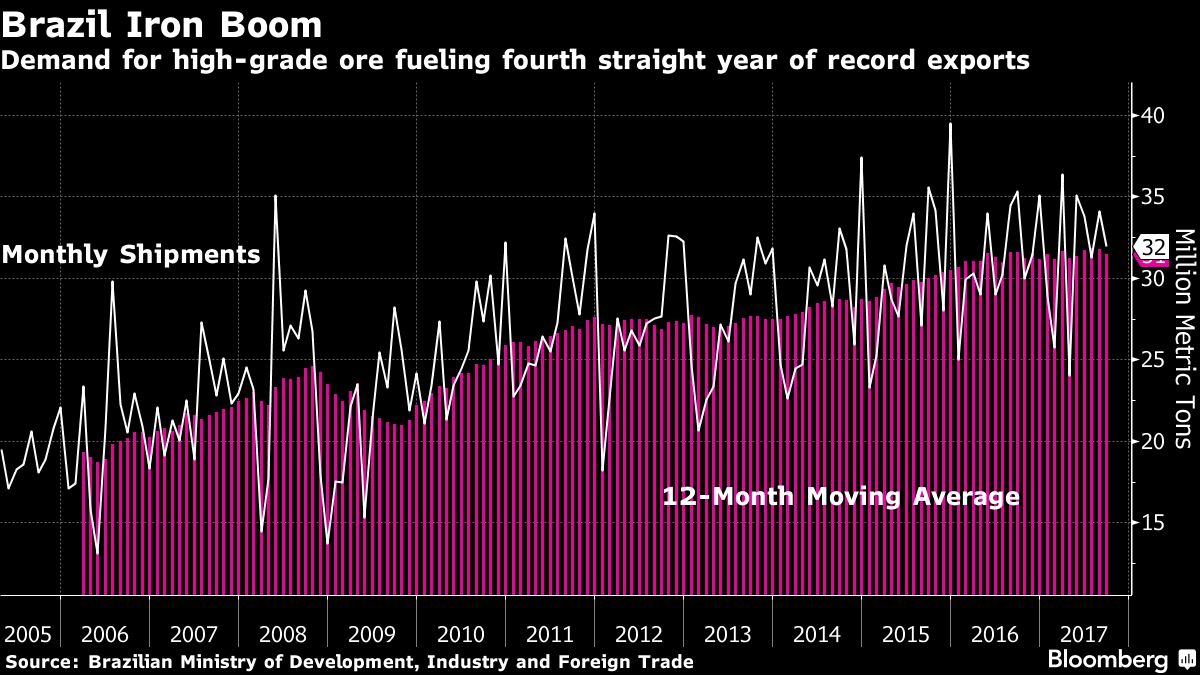

Exports by Brazil, one of the biggest suppliers, are headed for a fourth straight record in 2017. Top producer Vale SA is shifting production from low-grade reserves in the southeast that have been mined for a century to develop more high-grade deposits in the isolated northern regions of the Amazon, where environmentalists fear further damage to the world’s largest rainforest.

“It’s a contradiction,” said Frederico Martins, an official at the Brazilian government’s Chico Mendes Institute for Biodiversity Conservation who monitored Vale’s operations in the Amazon when he was managing the Carajas national forest for a decade. “China wants to clean up 20 years of pollution over there, yet impacting things more here.”

Vale iron ore processing at the Carajas mine in Brazil. Photographer: Paulo Fridman/Corbis via Getty Images

The incentive for Brazil to produce more is growing, especially for Vale, which is seeking to reduce $22 billion of debt it ran up during a three-year price slump that ended in 2016. The gap between low-grade and high-grade ore is widening to about $50 a metric ton from less than $10 about 18 months ago.

Ore that contains 65 percent iron sold for $86.50 a ton on Tuesday, compared with $36.96 for the lower-grade 58 percent ore, according to Metal Bulletin Ltd. The industry benchmark, based on 62 percent ore delivered to Qingdao, China, fetched $61.01.

Vale is ramping up its $14 billion project in the Amazon known as S11D, which began production earlier this year. The Rio de Janeiro-based company says better-quality reserves and more automated machinery mean the mine will eventually be able to produce ore at about $7 a ton. That’s less than half of its current total costs. Output at the site could reach 90 million tons a year by 2020.

The project marks the start of a transition from Vale’s origins in the southern state of Minas Gerais, where the company has more than 10 billion tons of known reserves. But most of those deposits don’t exceed 50 percent iron content. In Vale’s Amazon reserves, where S11D is located, it has almost 7 billion tons at more than 65 percent.

Export Surge

“Brazilian iron-ore shipments will grow significantly over the next four years,” as demand increases for higher-grade supplies, said Paul Robinson, director of non-ferrous metals at CRU Group, a mining-industry consultant based in London. Exports that are heading for a record 370 million tons this year may expand to 460 million or 470 million by 2021 as the premium continues to increase, he said.

The increased demand already is helping Vale. The company’s credit was upgraded to stable by Fitch Ratings Ltd., which forecast “reasonable profitability during periods of lower prices” as increased output from S11D boosts Vale’s advantage over rival exporters in Australia. Brazil currently accounts for about 22 percent of global iron-ore trade, and most of the country’s shipments come from Vale, according to Fitch.

Vale says it has reduced output of lower-grade ore by about 19 million tons a year while boosting supplies of the higher grades China is buying.

At a meeting with analysts last month, Vale Chief Executive Officer Fabio Schvartsman said reduced costs and the widening profit margins should help boost earnings before interest, taxes, depreciation and amortization by as much as $600 million in the second half of 2017. The company earned about $30 a ton last year, but Schvartsman said that profit could increase by as much as $6 a ton by 2020.

Retaining Talent

The outlook is improving because of the shift in buying by China, the world’s largest metals consumer and by far the biggest importer of iron ore. Only the country’s coal-fired electricity generators pollute more than its steel makers, according to Greenpeace. The government is closing the dirtiest plants and increasing commitments to expanded use of solar power and electric vehicles.

Aside from reducing costs associated with pollution, China also wants cleaner cities to retain the talents of its expanding middle class, which is better educated and more mobile, according to Matthew Kahn, a professor of economics at the University of Southern California in Los Angeles. He led a study examining the careers of politicians and mayors in 100 Chinese cities over eight years.

Vale mine in Brazil. Photographer: Yasuyoshi Chiba/AFP via Getty Images

“China’s original growth model was to have its own heavy factories in steel and other industries, and this created output and pollution,” Kahn said. “But now that China is transitioning to a human capital economy, smart, talented people want to live in cities with blue skies that look like San Francisco.”

The risk for Brazil is that it loses more of its rain forest, which Greenpeace estimates has shrunk by about a fifth in the past four decades as farmers moved in to plant soybeans or sugar and miners began digging up minerals.

In the Carajas national forest, where S11D is being developed, Vale says it protects about 8,200 square kilometers of natural habitat, or about five times the total area where it operates. The company has developed technologies and management systems to minimize the impact on the environment, its press department said by email.

Still, satellite images of the region show a dramatic amount of deforestation around locations where mining began in the 1980s. More than 40,000 people worked on developing S11D since 2010, and the company now employs about 2,700 workers full time, plus at least 10,000 indirect jobs.

“Mining attracts a migratory flow,” said Martins at the Chico Mendes Institute for Biodiversity Conservation, adding that the impact on rural areas is significant. “When the flow settles in the region, it does so in an irregular way, and that puts pressure on the forest as land is converted into rural and urban areas.”