Written by Laura Millan Lombrana. This article first appeared in Bloomberg News.

A little-known nuclear agency, designated as Chile’s lithium watchdog 38 years ago during the military dictatorship, holds the keys to unlocking the country’s massive reserves amid a nascent electric-car boom.

The Chilean Nuclear Energy Commission, or CCHEN by its Spanish initials, authorizes lithium quotas and exports in a throwback to a 1979 decision to declare lithium “strategic” because it was thought to be a key element in nuclear processes.

While that’s no longer the case, the government has no plans to remove CCHEN from lithium permitting even as authorities work on a new code for an industry struggling to keep up with growing demand from rechargeable batteries. More investor-friendly rules in Argentina have lured some interest away from Chile.

Jaime Alee, a professor who heads the Lithium Innovation Center in Santiago, sees no technical reason why lithium should be considered strategic or why CCHEN should control its extraction and sales. Lithium is found in several countries, but only Chile and Bolivia require a special authorization, he said.

“It makes no sense,” Alee said. “But changing its status means changing the law, which could take from three to four years and there’s no time for that. So the most practical option is to work with what we have.”

While lithium is used in nuclear reactors for regulation of water chemistry, it isn’t used as a power source for nuclear fission, said Jonathan Cobb, communications manager at the World Nuclear Association in London.

The industry’s focus has shifted from reactors to batteries, as carmakers such as Tesla Inc. push to bring electric vehicles to the mass market.

In Chile, lithium producers must get a license from both CCHEN and the Mining Ministry. The Ministry hasn’t awarded a permit in more than two decades, while CCHEN has only ever approved new quotas for incumbents Albemarle Corp. and Soc. Quimica & Minera de Chile SA, as well as state copper producer Codelco.

A number of prospective new players are waiting for the new lithium rules to apply for their own licenses. Still, the nuclear agency’s role won’t change.

“We will make no changes to CCHEN in the short term,” Mining Minister Aurora Williams said in an interview last month. “We think it’s reasonable that CCHEN verifies lithium extraction quotas, as well as transactions.”

In a country with no nuclear energy plants, the main role of the agency’s more than 300-strong workforce is to supervise the use of radioactive material in hospitals and the food industry.

While a chemical engineer was hired last year to support the agency’s role in lithium, CCHEN has no formal lithium division and there’s no mention of the soft, silver-white metal in its mission and vision statements, nor in its key performance indicators for 2018. Three of the agency’s seven board members are military officials, according to the agency’s website.

CCHEN doesn’t have enough specialized technical expertise in lithium, according to Alee, who has advised the agency in the past. Its role in lithium was purely administrative before it became a key component in batteries for electric cars.

The agency declined to respond to criticism of lithium’s strategic status and its role in permitting.

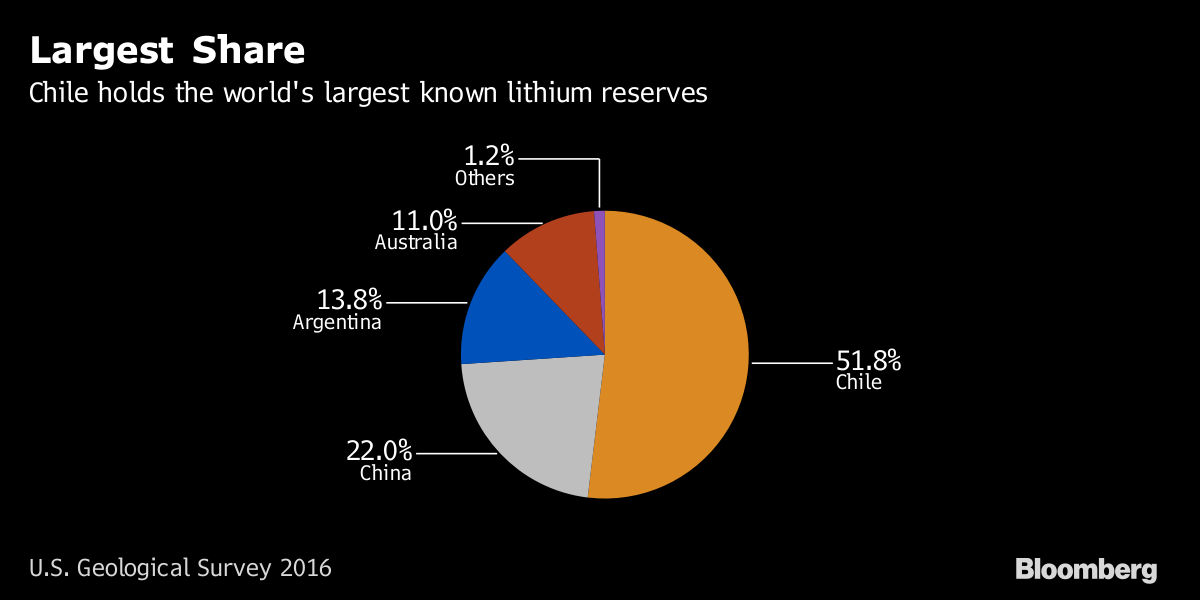

Globally, lithium supply growth may be too slow, creating bottlenecks that pose “serious risks” to the future of mass adoption of electric vehicles, Goldman Sachs Group Inc. said in a note last week. Producing more from the vast salt flats of Chile’s northern deserts could reduce those risks.

CCHEN doesn’t have a set of criteria for those seeking licenses. Instead, it asks companies to present legal and technical information, Patricio Aguilera, the agency’s executive director, said in an emailed response to questions. Terms for different licenses aren’t necessarily comparable because they depend on the records given by each company, he said.

“CCHEN respects the principle of equality under the law and has essentially requested the same technical information since 2010,” Aguilera said. “CCHEN is not considering changes to the process of awarding licenses over the short term.”

Permitting Differences

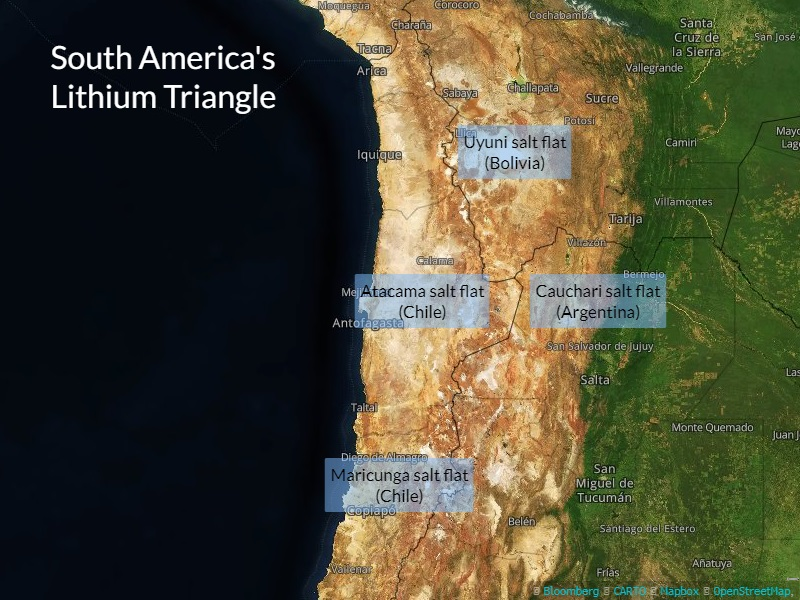

Documents obtained through freedom of information requests show the differences between permits awarded to Albemarle to increase production in the Atacama salt flat and those granted to Codelco for Maricunga, where the state miner is seeking private-sector partners to start producing.

In a three-month process, Codelco obtained a quota — transferable to third parties — to produce 325,045 tons over 40 years, the documents show. Albemarle’s process took five months, with the Charlotte, North Carolina-based company granted a 540,240-ton non-transferable quota over 27 years. Unlike Codelco, Albemarle already had mining rights in the area and submitted environmental and reserve studies.

“The rules aren’t clear, strange things have happened in these processes that have no explanation,” Alee said. “I don’t think this situation is very sustainable, but changing it takes political will.”

For questions related to information in this article, please contact the authors directly.