After nearly two years of constant crisis, the German car industry is looking to salvage its beleaguered diesel technology and draw a line under an emissions scandal that shows no signs of abating.

At an emergency summit in Berlin called by the government, the chief executives of Volkswagen AG, Daimler AG and BMW AG will face off with ministers and state leaders to convince them that, despite the steady drumbeat of negative news, diesel has a future. In return for political support to avoid driving bans, automakers are willing to further upgrade existing vehicles to lower their pollution.

There’s a lot at stake for all sides. German automakers need diesel as a stop-gap technology to buy time to catch up with the electric offerings of Tesla Inc. and Nissan Motor Co. And with less than two months until a federal election, Chancellor Angela Merkel, whose ruling bloc runs the ministry overseeing carmakers, has to ward off criticism that the government is too lenient on carmakers while also not endangering the country’s 800,000 industry jobs.

“The manufacturers will play their part to improve air quality in cities and make diesel fit for the future,” said Matthias Wissmann, head of German auto lobby VDA, proposing reduction in nitrogen-oxide emissions of at least 25 percent on average. “Diesel is enormously important for climate protection as well as prosperity in Germany.”

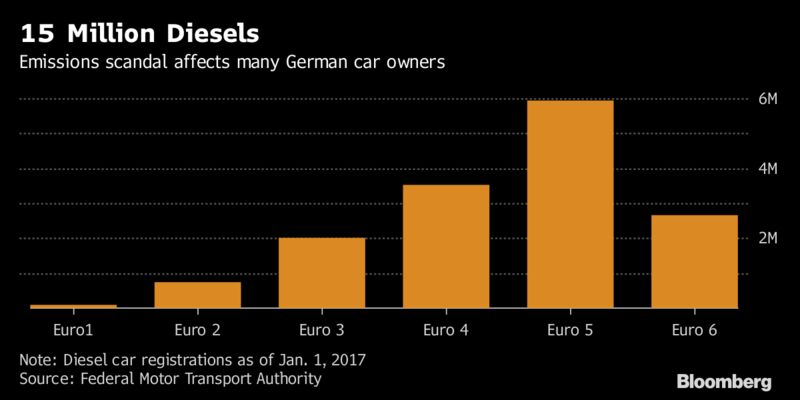

The two sides are expected on Wednesday to agree to a host of measures designed to lower emissions of nitrogen oxides, which cause smog and health problems, in Germany’s 15 million diesels. In the run-up, carmakers and the government were haggling over software fixes — costing several hundred million euros — and much more expensive hardware changes that would lift the total bill to around 5 billion euros ($5.9 billion). Much of that would be born by the companies.

“I think this is a result that is achievable today because everyone knows that it will otherwise be legally enforced, so this part is clear,” Armin Laschet, premier of the state of North Rhine-Westphalia and member of Merkel’s party, said on ZDF television on Wednesday, when asked if carmakers will bear the full cost of diesel modifications.

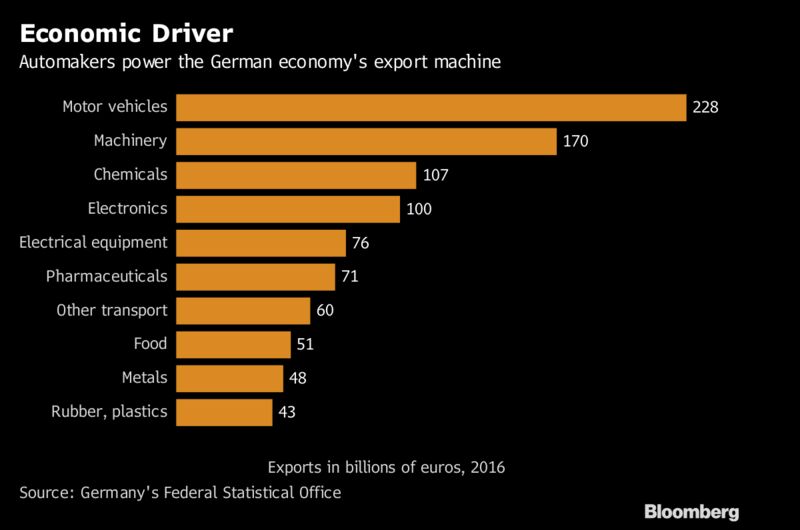

Dealing with the crisis is a difficult balancing act in Germany, where every fifth job depends on the industry and the sector accounts for more than half of the country’s trade surplus. Last year, some 46 percent of the cars sold in the country had a diesel engine. The turmoil compounds an already tense time for the industry that’s struggling with the switch to electric cars and a host of new challengers like Tesla, Uber Technologies Inc. and Apple Inc. readying their strategies for a slice of future profits.

“The significance of the car industry is extremely high. VW is more important to Germany’s economy than Greece,” said Carsten Brzeski, Frankfurt-based chief economist at ING-Diba AG. “The industry has to find a solution together with government over how to face the big questions head on around the structural transformation.”

The relationship between the industry and politicians in Germany has also come into focus during the scandal, with critics questioning why it’s taken Transport Minister Alexander Dobrindt, who called Wednesday’s meeting, nearly two years to take decisive action after U.S. authorities exposed VW’s emissions cheating in September 2015.

Carmakers, and especially Germany’s premium manufacturers, need diesel to power their luxury sedans and a growing fleet of fuel-guzzling sport utility vehicles, as consumers remain reticent to buy a sparse lineup of electric cars. Diesel emits about a fifth less of the greenhouse gas carbon dioxide compared with equivalent gasoline engines, making the technology key in meeting the European Union’s tough emissions regulation, which will tighten further beginning in 2020.

To shore up diesel, BMW, Daimler and Volkswagen have announced voluntary recalls of several million cars with newer Euro 5 and Euro 6 emissions standards, costing less than 100 euros per car. The expected reduction in nitrogen oxides — about 20 percent — isn’t enough to clean up city centers, according to environmental advocacy group Deutsche Umwelthilfe, which last week won a case at Stuttgart administrative court seeking broad diesel bans for Daimler’s and Porsche’s hometown.

“The political system, the parties, the government in Germany has part of the responsibility for the current situation,” Ferdinand Dudenhoeffer, director of the University of Duisburg-Essen’s Center for Automotive Research, said in an interview with Bloomberg TV. “Our politicians and our car industry want to save the past,” but “diesel is a mess, and they need to find a solution for the future.”