Written by Ewa Krukowska. This article first appeared in Bloomberg News.

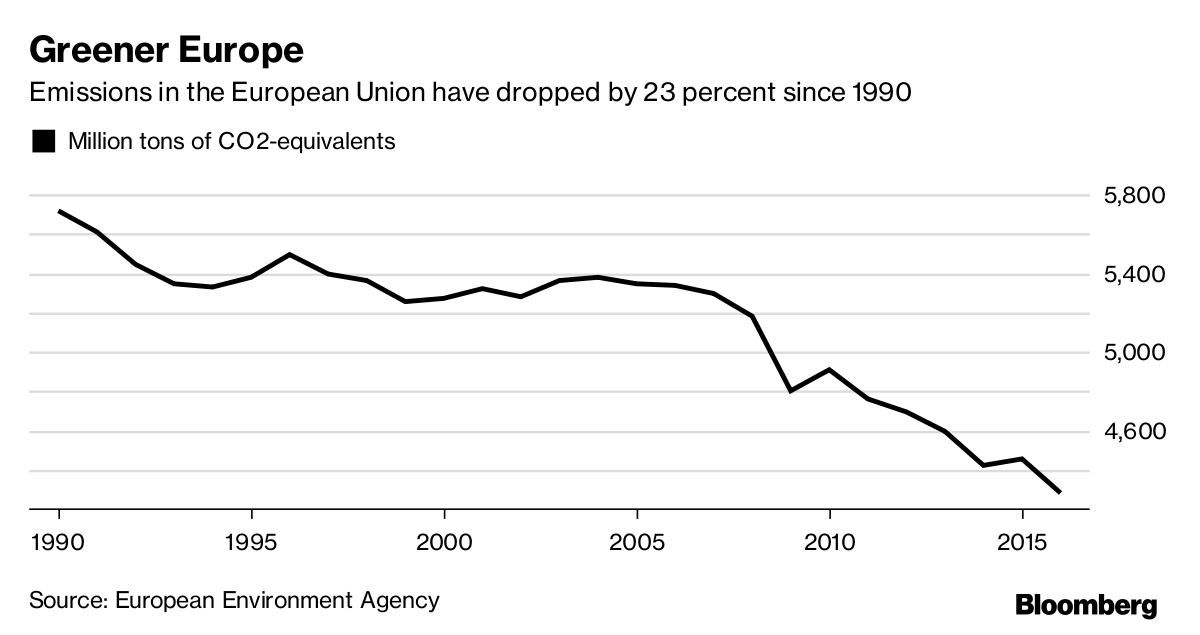

Europe is stepping up its efforts to cut pollution, and companies across the continent are facing a growing bill unless they go cleaner.

European Union policy makers reached a provisional deal last week to overhaul the bloc’s Emissions Trading System, the world’s biggest carbon market. Under the accord, companies will have to reduce greenhouse-gases by 43 percent by 2030 compared with 2005 levels, while a mechanism to curb the glut of pollution permits will be strengthened, bolstering their prices.

The EU cap-and-trade program for emissions is the cornerstone of the region’s plan to cut greenhouse gases that scientists blame for global warming. It imposes annually decreasing pollution limits on power producers, airlines and industries from steel to cement makers. For every metric ton of carbon dioxide they discharge, emitters have to submit one emission permit, bought or received for free, or pay a fine of 100 euros ($117) per ton. Companies that pollute less than their cap can sell excess permits, getting an incentive for going greener.

“The reform will put more pressure on industry to decarbonize,” said Jahn Olsen, an analyst at Bloomberg New Energy Finance in London. “In early 2020s the impact may be somewhat muted because the largest emitters build up a surplus of permits, but later on the industry will certainly have to reduce emissions beyond business-as-usual efficiency improvements. The planning has already started.”

As of 2021, the annual emissions caps on around 12,000 facilities owned by manufacturers and utilities from Electricite de France SA to Germany’s EON SE to Poland’s PGE SA will decrease faster. The tougher limits will save the planet from an additional 556 million metric tons of carbon-dioxide over the next decade, equivalent to the annual emissions of the U.K. Free allowances will still be handed out, but will be targeted to industries at a higher risk of relocating outside Europe, while financial aid for upgrading energy infrastructure will be subject to stricter environmental criteria.

The full details of the Nov. 9 agreement between EU governments, the European Parliament and the European Commission haven’t been published yet. Bloomberg News talked to policy makers with knowledge of the negotiations about the most important provisions in the deal.

Cap-and-Trade

Under the accord, the rate at which the pollution cap on companies falls each year will be 2.2 percent, starting in 2021. That compares with the so-called Linear Reduction Factor of 1.74 percent in the current trading period from 2013 to 2020.

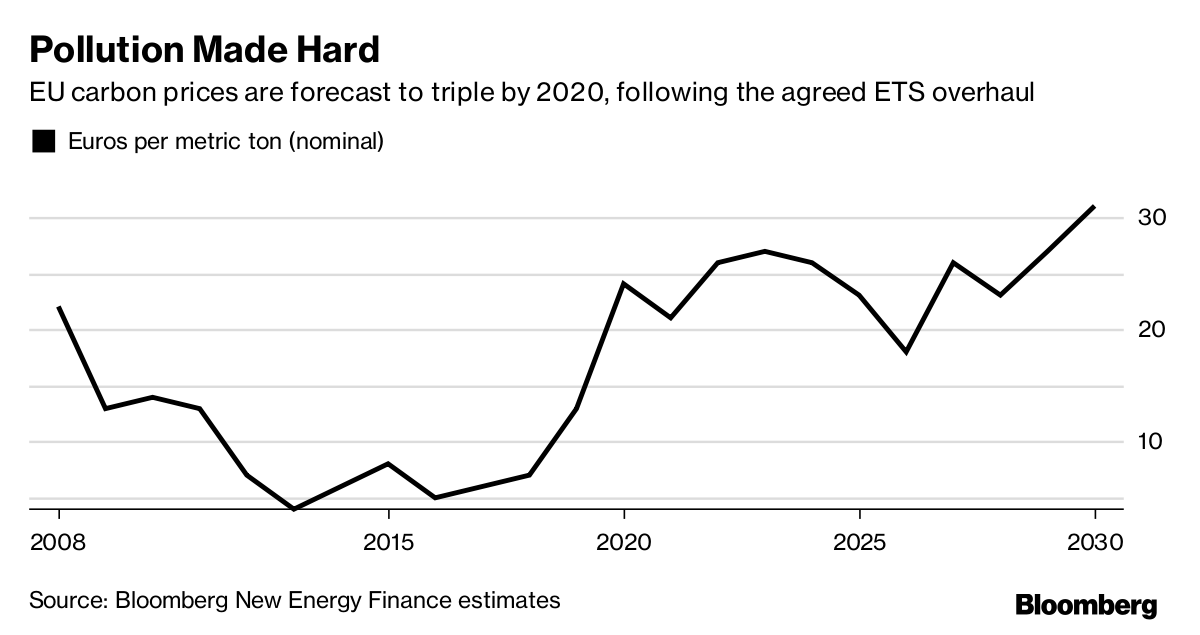

A market glut that pushed carbon prices almost 70 percent down since the start of 2008 will shrink, thanks to the strengthening of a mechanism that absorbs excess permits from the market. The volume swept into the so-called Market Stability Reserve will double to 24 percent of permits in circulation over a five-year period, starting in 2019.

“This is a very bullish scenario, because once the MSR kicks in you’ll really going to be taking a massive amount of supply out of the market,” said Mark Lewis, managing director and head of European utilities research at Barclays. “Based on what we know today, I think we can see carbon permit prices at 20 euros a ton in 2020, and maybe already 15 euros a ton in 2019 and probably 10-12 euros per ton by the second half of next year as the market starts to anticipate.”

Some excess allowances will be invalidated. From 2023, permits in the reserve will start expiring if they exceed the amount sold at auctions in the previous year.

Still, environmental lobbies criticized the reform for lacking ambition. “If EU emissions continue to fall at their historic average rate, the reform still leaves a surplus of around 2 billion tons of CO2 available to the carbon market in 2030,” according to Sandbag, a not-for-profit climate change policy think tank, based in Brussels. “This would prevent the EU ETS carbon price rising significantly.”

Free Allowances

In the so-called Phase 4 of the market, from 2021 to 2030, 57 percent of allowances will be sold at government auctions and 43 percent will be given for companies for free. While the proportions don’t change compared with the current phase, fewer free allowances will be handed out for sectors less exposed to the so-called carbon leakage phenomenon, where businesses move their production beyond Europe to avoid emission limits. The free allocation rate for companies not at significant risk of fleeing will initially be 30 percent, before it starts to be phased out after 2026.

The overhaul will also introduce a flexibility mechanism to avoid losing free allowances when the Cross-Sectoral Correction Factor is triggered. That’s a mechanism that slashes the number of such permits across industries if the total number of free allowances requested by governments exceeds the maximum allowed under EU law. Should the CSCF kick in, the share of allowances to be auctioned will be lowered by 3 percent.

EU nations will continue to be able to offer financial compensation to energy-intensive companies for the so-called indirect emission costs, or pollution-reduction costs incurred by electricity suppliers and passed on to industries in power prices. Such compensation has to be in line with EU public aid rules.

Financial Support

As many as 835 million allowances, which may be worth 20 billion euros in 2020 according to BNEF’s forecasts, will be earmarked for two funds that will support the shift to low-carbon economy. Those permits will be auctioned, with the details of the process yet to be agreed.

- The Innovation Fund will help finance investments in renewable energy, carbon capture, and storage and innovation in energy-intensive industries. It will consist of 400 million permits, with an option of increasing that by an additional 50 million.

- The Modernization Fund is to support 10 poorer EU nations: Bulgaria, Croatia, the Czech Republic, Estonia, Hungary, Latvia, Lithuania, Poland, Romania and Slovakia. It will be handed 310 million allowances, which can be conditionally increased by 75 million permits. No aid will be given to projects involving solid fossil fuels, such as coal, which Poland wanted to be eligible for funding. An exception was made for investments in district heating in Romania and Bulgaria. “We will make a final statement about the ETS reform after a proper assessment of the text,” said Poland’s EU affairs minister Konrad Szymanski.

“They found the right balance between protecting the industry and safeguarding the future of the ETS as a tool to protect the climate,” said Marco Mensink, director general of the European Chemical Industry Council, which represents manufacturers such as BASF SE, Akzo Nobel NV and DowDuPont Inc. “Negative reaction by some industries originates from not understanding the political pressure to change the system.”