This article was written by Kobad Bhavnagri, Head of Strategy for BloombergNEF. It appeared first on the Bloomberg Terminal.

- World needs IMF-like institution to fund nature protection

- Adding biodiversity to balance-sheets can change conversation

There is one essential reason why the world’s rainforests continue to shrink: We aren’t paying for them.

Over the years there have been countless well-intentioned efforts to prevent their destruction, but at the aggregate level, all of these are failing. The rate of forest loss has hardly slowed over the last 10 years, with around 7 million hectares vanishing every year.[1]

There is a simple economic reason why. A hectare of rainforest that is converted to soy, palm oil or beef pasture can earn a farmer a profit of around $500 per year. A hectare of rainforest kept as rainforest earns a landholder next to nothing, in most circumstances.

This is a clear economic failure. If we are to have any chance of halting the climate and biodiversity crises that threaten our welfare and prosperity, that needs to change. Urgently. The good news is that we know how.

Time to pay our way

This is not an argument about environmental ethics, as important as that is. The world’s rainforests have huge economic value. Combined they contain around 50% of the Earth’s species and store 40% of terrestrial carbon.[2] They provide fresh water, host pollinators, manage nutrients and are a rich genetic library for medicines. All of these services are worth around $4,741 per hectare, per year by one estimate.[3]

Putting it another way, the rainforests are an asset that provide us critical services. Continuing to lose them will make us poorer, because it will cost us more to replicate the services they supply through synthetic means, like with machines. We also can’t viably mimic everything nature provides.

As the old saying goes, you get what you pay for. If we don’t start recognizing the value of the rainforest’s services – and reward their hosts for what they provide – we are going to keep losing them. Eminent economists like Partha Dasgupta make the same argument: “If we are to preserve the world’s rainforests, the global community should be prepared to pay the nations harbouring them to do that”.

So how much do we need to pay? At the most basic level, a landholder needs to be paid the opportunity cost of that land, or the amount of profit they could earn from converting the rainforest to something else, which is usually agriculture. A rough rule of thumb is that a farmer in the tropics can earn $500 profit per hectare, per year.

How can we make that flow? There are three potential approaches.

Markets for protection

Landholders that host the rainforests can be renumerated via markets that place a value on their global services, like carbon sequestration and biodiversity provision. Indeed a framework to do this, known as REDD+, already exists.[4] The trouble is that its prices are too low and it is focused almost entirely on carbon.

Demand for REDD+ carbon credits has been growing fast, but remains small. Some 69 million credits (each representing a ton of CO2) were retired in 2021, at an average price of $4.73 per ton.[5] This equates to around $71 of revenue per hectare of rainforest protected, substantially less than the roughly $500 profit per hectare that can be earned from agriculture.

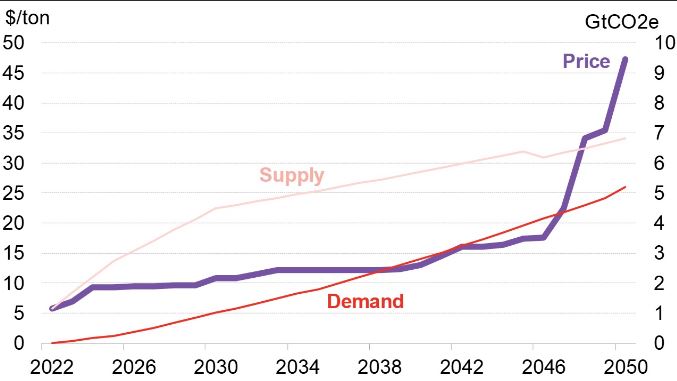

To provide sufficient incentive to landholders to forgo agriculture, the price of a REDD+ carbon certificate needs to rise to around $33 per ton. BNEF’s analysis of market fundamentals suggests that is unlikely to happen on carbon value alone, because the huge potential supply of forestry credits will suppress prices, if buyers continue to accept their use.[6]

For REDD+ to effectively protect the rainforests, the biodiversity value of credits must become the core driver of price; or another market for biodiversity credits needs to form. Demand also needs to scale up – around 27 billion REDD+ certificates would need to be bought to protect the rainforests that remain in their entirety, and go even higher to restore forest already lost.

Carbon offset prices, supply and demand under the voluntary market scenario

A World Bank for Nature

Another approach is to create a global institution like a World Bank or International Monetary Fund to fund the protection of nature. This is an idea floated by Dasgupta in his landmark review on the economics of biodiversity.2

This body would disburse funds to countries that host crucial biomes like the rainforests, which are in effect global public goods, as every country benefits from their existence. Dasgupta suggests this could be funded from a levy on ships using international waters – a global common which is currently free to exploit.

To have any chance of gaining acceptance, the charges on shipping and fishing would need to be trivially small. My calculations suggest that a 1% levy on the 11 billion tons of ocean freight moved each year would raise only $500 million. Likewise, a $0.1/kg levy on the 4 million metric tons of seafood caught from the high seas would yield only $400 million. Combined, this would be enough to protect just 1.8 million hectares of rainforest.

To be effective, billions would need to be raised from other sources too. Aside from government contributions, logical candidates would be other products that cause nature loss like plastics and pesticides, or high-margin beneficiaries of nature’s genetic resources, like the pharmaceutical sector.

Putting nature on the balance sheet

A less direct route is to recognize the economic value of the rainforests on corporate balance sheets and in national accounts. Today, destroying 1,000 hectares of rainforest to build a cattle ranch always looks like an economic positive because traditional measures of wealth (like gross assets, gross domestic product and national net wealth) only value the increase in cows, farmland and buildings. The economic value of the rainforest that was lost, and the services it provided, doesn’t show up. It’s a classic case of ‘you can’t manage what you don’t measure’.

If corporations and governments were to formally measure the change in natural capital that occurred when 1,000 hectares of rainforest were cleared, they would have to recognize that growth in produced assets or capital needs to be balanced against the depreciation of natural capital.

More than 34 countries have begun incorporating natural capital and the flow of ecosystem services into their national metrics, including the UK, New Zealand and China, and the UN has adopted a new framework to integrate natural capital in economic reporting.[7] Natural capital accounting in corporations could well see a boom due to the development of the Taskforce for Nature-related Financial Disclosures (TNFD), a comprehensive framework to consider nature-risk.

But how can this be turned into dollars? The answer is through risk. Municipal bond markets are already starting to price in natural capital following extreme weather events.[8] Trillions of dollars of bonds issued by countries and companies have also been identified as exposed to natural capital risks.[9],[10] In other words, countries and companies that manage their natural capital poorly can expect to pay more on their debt, and doubtless in time that will affect equity valuations too.

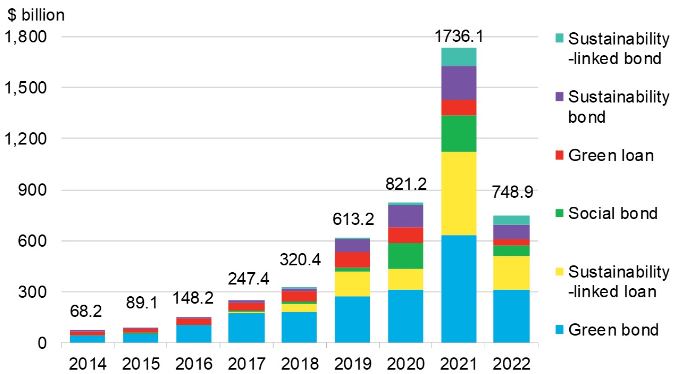

The other side of risk is opportunity. Including natural capital can boost measures of national wealth by as much as 40% for developing countries. 2,[11] Recognition of this wealth and good management of nature should in time logically lead to a reduction in sovereign risk ratings and lower the cost of debt. Sovereign debt can also be forgiven, as happens with debt-for-nature swaps. New types of finance can also be raised – the first forest bond was issued in 2016 and the broader category of sustainable debt totaled $1.7 trillion dollars in 2021.[12] As these instruments and markets develop, governments may find new ways to derive revenue from keeping rainforests intact. It may not result in $500 payments per hectare to landholders, but the incentives it creates for governments would be strong.

Annual sustainable debt issuance

A $500+ billion opportunity beckons

If the great tropical rainforests are to be protected, it is likely that some combination of the above three approaches will be required.

How much in total is needed? Most estimates suggest around $500 billion per year.1,[13] But even a fraction of this can make an immediate difference. Some $50 billion per year should be enough to fund the opportunity cost of around 100 million hectares to landholders, or around 10% of tropical rainforest at the greatest risk at the edges of the Amazon, Congo and across South East Asia.

This underscores that the rainforests are a huge opportunity for the countries that host them. Once their value is recognized, Brazil, the DRC, Indonesia and their neighbors will be core beneficiaries.

When will this happen? When the world gets serious about biodiversity loss. There are high hopes that this moment will come when the Convention on Biological Diversity meets in Montreal in December this year, but that is by no means guaranteed. The public and private sector needs to push hard for a ‘Paris agreement for nature’ to be struck there, including a target to protect 30% of land and sea for nature, backed by real investment mechanisms like the three profiled above.

The fundamentals are clear. Tens and then hundreds of billions of dollars must ultimately flow to protect the crucial biomes on which humanity relies. The risk and opportunities are too big to ignore.

[1] Forest Declaration Assessment: Are we on track for 2030, Forest Declaration Platform, 2022

[2] Dasgupta, P., The Economics of Biodiversity: The Dasgupta Review, Her Majesty’s Treasury, 2021.

[3] Ecosystem Services Valuation Database, Foundation for Sustainable Development, 2021. Estimate for the Amazon.

[4] REDD+ stands for: Reducing emissions from deforestation and forest degradation and the role of conservation, sustainable management of forests and enhancement of forest carbon stocks in developing countries.

[5] BloombergNEF, Long-Term Carbon Offsets Outlook 2022

[6] A growing number of schemes and initiatives only permit offsets that represent a ton of carbon removed from the atmosphere. REDD+ credits represent a ton of carbon emissions avoided.

[7] United Nations, UN adopts landmark framework to integrate natural capital in economic reporting, March 2021.

[8] Rizzi, C., Nature as a Defence from Disasters: Natural Capital and Municipal Bond Yields, 2022.

[9] London School of Economics, The sovereign transition to sustainability, 2020.

[10] Moody’s Investor Service, $2.1 trillion of rated debt highly exposed to natural capital impact or dependency, June 2021.

[11] World Bank Group, The Changing Wealth of Nations, 2021.

[12] BloombergNEF, 2H 2022 Sustainable Finance Market Outlook: Trend Change

[13] See for example: Conant, J., van der Mark, M., Financial Incentives To Slow Deforestation Are Helpful – But Public Policies To Stop It Are Essential, Forests & Finance, November 2021.