Mark Schneider, chief executive officer of Nestle SA, had a prescient message when he spoke at a German consumer goods forum last month.

“Size alone does not protect you from the winds of change,” Schneider said. “Status quo is not an option.”

Unbeknownst to his audience, shareholder activist Daniel Loeb was about to announce that his new target was the biggest Swiss company by market value. A tremor went through corporate Switzerland three days later when Third Point, Loeb’s firm, revealed a $3.5 billion stake and demanded that Nestle buy back shares and boost sales growth, which had slowed to the weakest in more than a decade.

Swiss companies need to up their game or they will attract further approaches, according to Nuno Fernandes, a professor at IMD business school in Lausanne. Investors are exploiting legal changes implemented three years ago that give them more power to fire board members and cut CEO pay in the country that has the highest executive compensation in Europe.

“The only way Swiss companies can avoid being targeted by activists is generating above-average returns,” Fernandes said. “It’s no longer possible for them to hold business units with returns below the cost of capital.”

The most recent case of shareholder activism came earlier this month, when two U.S. investment managers said they acquired about 7.2 percent of Swiss chemicals maker Clariant AG in a bid to undo its planned $6.4 billion takeover of Huntsman Corp.

Earlier this year, Credit Suisse Group AG trimmed bonuses by 40 percent to respond to criticism from investors including Norway’s sovereign wealth fund after two years of losses.

‘Great Place’

“Switzerland is a great place for activists,” said hedge fund manager Rudolf Bohli, who manages 250 million francs ($260 million) at RBR Capital Advisors near Zurich. He said he’s seeking another target after failing in his bid to oust Alex Friedman, CEO of asset manager GAM Holding AG. “Swiss chairmen are among the most overpaid in Europe. I think the Loeb move may motivate other investors.”

The upsurge in activism stems from a referendum four years ago. In the wake of an abandoned proposal to pay out $78 million to departing Novartis AG Chairman Daniel Vasella, Swiss voters backed a plebiscite to beef up shareholder rights.

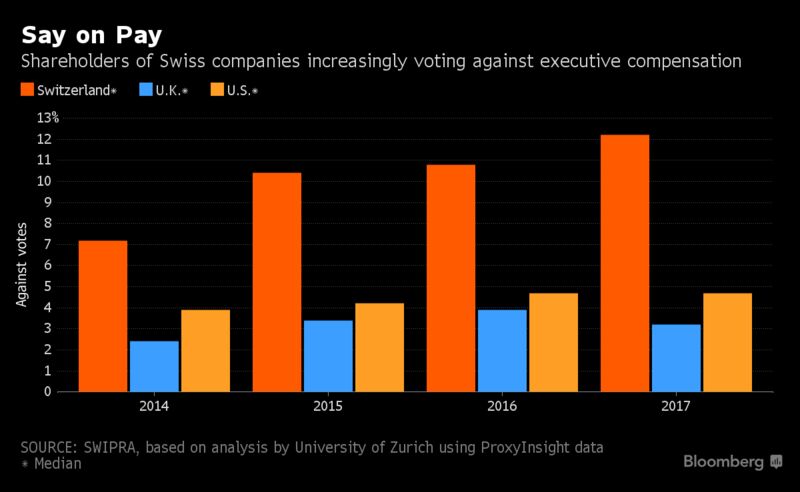

Now Switzerland is one of the few countries where shareholders have a binding vote over how much money the board and CEOs get, whereas in the U.S. and the U.K., such votes are only consultative. Plus, every board member’s seat goes up for reelection each year. Besides severely lengthening annual general meetings, that gives shareholders the potential to fire a company’s leadership en masse. Executives who fail to abide by the rules can face criminal prosecution.

“Switzerland’s probably got some of the more stringent rules, globally,” said Justin Szwaja, who covers corporate governance at Ernst & Young in Geneva. “It went from zero to hero, going from a softer law and a code of best practice, to having binding votes.”

That led to seven activist campaigns in 2015, following half a decade during which the number ranged from zero to three a year, according to a report by law firm Skadden, Arps, Slate, Meagher and Flom LLP. The most prominent battles were Knight Vinke Asset Management pushing UBS Group AG to spin off its investment bank and Cevian Capital AB building a stake in ABB Ltd. in a move that eventually gave the firm a board member.

“After the activists’ stakes in Nestle and Clariant-Huntsman became public, we have seen a significant increase in calls from clients seeking advice on how to prepare for when these investors knock on the door,” said Hernan Cristerna, London-based global co-head of M&A at JPMorgan Chase & Co., which has a team of about 15 people covering activism. “It used to be bankers pushing companies to prepare for it. Now it’s companies proactively asking for advice.”

Switzerland prohibits companies from using poison-pill measures to dilute the stake of hostile parties, leaving them with few defenses against activists except for voting right limitations.

Erik Fyrwald, CEO of Syngenta AG, said activism can divert companies from their long-term strategies. In 2015, the Swiss agrochemicals maker faced dissent from a shareholder group upset at its refusal to engage with Monsanto Co. over a $47 billion takeover approach. Fyrwald said he values China National Chemical Corp.’s more-patient approach because it can take a decade to develop a new pesticide or a new genetically modified seed.

“Activist shareholders put a lot of pressure on companies, often to the detriment of the long-term investment,” the CEO said in an interview in Brussels. “Most activist shareholders do not have a 10-year view.”

Still, Swiss politicians haven’t reacted to the recent wave of activism, and are unlikely to, at least in public, according to Hans-Jakob Diem, an M&A lawyer at Lenz & Staehelin.

“It’s a very liberal jurisdiction,” he said on a conference call. “If markets dictate, then the market wins.”